| Issue |

BSGF - Earth Sci. Bull.

Volume 196, 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | 6 | |

| Number of page(s) | 60 | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/bsgf/2024027 | |

| Published online | 04 June 2025 | |

Coral biodiversity from Morocco after the End-Triassic mass extinction

Biodiversité corallienne du Maroc après l’extinction de masse du Trias-Jurassique

1

University of Geneva, Department of Earth Sciences, Rue des Maraîchers 13, 1205 Geneva, Switzerland

2

Université de Lorraine, CNRS, lab. GeoRessources, UMR 7359, BP 70239, 54506, Vandoeuvre-lès-Nancy Cedex, France

* Corresponding author: simon.boivin@unige.ch

Received:

20

January

2024

Accepted:

13

November

2024

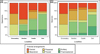

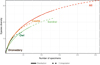

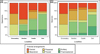

Each new coral-bearing outcrop found in Lower Jurassic strata is useful to understand the evolution of corals between the end-Triassic mass extinction and the Toarcian anoxic event. Here we provide new taxonomic data on corals issued from fieldwork on four outcrops from the region of Amellagou, in the High Atlas Mountains, Morocco. A set of 157 coral specimens have been collected from a small biostrome, a giant reef and two olistholiths, spanning from Hettangian − Sinemurian time interval to early Pliensbachian. These corals are distributed in 14 families, 22 genera and 27 species. Among these species, two are new: Lepidophyllia (Heterastraea) microcalix sp. nov., represented enough to allow a population study and Paracuifia castellum sp. nov. The study extends the last appearance datum of several genera known only in the Triassic till now, namely: Parastraeomorpha, Araiophyllum, Paracuifia, Pinacophyllum and, possibly, Paravolzeia. For this reason, the severity of the end-Triassic mass extinction is questioned in comparison to the extinction events that happened around the Pliensbachian-Toarcian boundary. For this reason, moreover, the phyletic discontinuity between some Triassic and Jurassic taxa is also addressed. Some Lazarus taxa known from Triassic and Pliensbachian remain absent in Hettangian and now, at a lesser degree, in Sinemurian. That is why we assume that the absence of these taxa is only due to the poor preservation of coral environments during these times. This study also changes our view on the first appearance datum of several genera that were known in Jurassic strata, namely: Proleptophyllia, Vallimeandropsis and, possibly, Lochmaeosmilia. A special attention is given to the distribution of colonial arrangements and points to the important proportion of cerioid and solitary corals. Additionally, the study highlights the existence of significant proportions of thamnasterioid and meandroid forms. The presence of corals with such a level of integration, together with the occurrence of two species that show platy to ramose transition in their colony shape, namely Hispaniastraea murciana and Chrondrocoenia clavellata, stresses the effectiveness of a photosymbiosis in these Early Jurassic coral communities. Lastly, the proportion of solitary specimens increased over time, revealing the uniqueness of coral assemblages during the Pliensbachian.

Résumé

Chaque nouvel affleurement corallien découvert dans les strates du Jurassique inférieur est utile pour comprendre l’évolution des coraux entre l’extinction de la fin du Trias et l’événement anoxique du Toarcien. Nous fournissons ici de nouvelles données taxinomiques sur des récoltes de coraux issues de travaux de terrain sur quatre affleurements de la région d’Amellagou, dans les montagnes du Haut Atlas, au Maroc. Un ensemble de 157 spécimens de coraux a été collecté provenant d’un petit biostrome, d’un récif géant et de deux olistolithes s’étendant de l’intervalle de temps Hettangien −Sinémurien au Pliensbachien inférieur. Ces coraux sont répartis en 14 familles, 22 genres et 27 espèces. Parmi ces espèces, deux sont nouvelles, Lepidophyllia (Heterastraea) microcalix nov. sp., suffisamment représentée pour permettre une étude de population et Paracuifia castellum sp. nov. L’étude étend la dernière apparition de plusieurs genres connus jusqu’à présent seulement dans le Trias, à savoir : Parastraeomorpha, Araiophyllum, Paracuifia, Pinacophyllum, et peut-être Paravolzeia. Pour cette raison, la sévérité de l’extinction de la fin du Trias est remise en question par rapport aux événements d’extinction qui se sont produits autour de la limite Pliensbachien-Toarcien. Pour cette raison aussi, la discontinuité phylétique entre certains taxons du Trias et du Jurassique est également remise en question. Des taxons Lazare connus du Trias et du Pliensbachien restent absents dans l’Hettangien et maintenant à un moindre degré dans le Sinémurien. C’est pourquoi nous supposons que l’absence de ces taxons est uniquement due à la mauvaise préservation des milieux coralliens à ces époques. L’étude change notre point de vue sur la date de première apparition de plusieurs genres qui étaient connus dans les strates jurassiques, à savoir : Proleptophyllia, Vallimeandropsis, et peut-être Lochmaeosmilia. Une attention particulière est accordée à la distribution des arrangements coloniaux et souligne la proportion importante de coraux cérioïdes et solitaires. De plus, l’étude souligne l’occurrence de proportions non négligeables de formes thamnastérioïdes et méandroïdes. La présence de coraux avec un tel niveau d’intégration, ainsi que l’occurrence de deux espèces qui montrent une transition lamellaire à rameuse dans la forme de leur colonie (Hispaniastraea murciana et Chondrocoenia clavellata), indiquent l’efficacité d’une photosymbiose dans ces communautés coralliennes du Jurassique inférieur. La proportion de spécimens solitaires a augmenté avec le temps, ce qui indique la singularité des assemblages coralliens au cours du Pliensbachien.

Key words: Scleractinia / Morocco / Early Jurassic / extinction / biodiversity / recovery

Mots clés : Scleractinia / Maroc / Jurassique inférieur / extinction / biodiversité / récupération

© S. Boivin et al., Published by EDP Sciences 2025

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

1 Introduction

The beginning of the Early Jurassic is classically considered a difficult time for corals and therefore for reefal ecosystems in which corals have always played an important role throughout the Phanerozoic. This epoch was even referred to a “reef gap” (Flügel and Kiessling, 2002) or more softly to a “reef eclipse” (Stanley, 1992, 1997, 2001). The reality is that this period of reef disturbance occurs between two extinction events. Corals faced a first severe extinction at the end of the Triassic (Kiessling et al., 2007; Lathuilière and Marchal, 2009), then a second severe multiphased extinction at the end of the Pliensbachian (Vasseur et al., 2021). Consequently, the discovery of new coral records in the Hettangian, Sinemurian and Pliensbachian is still important for understanding corals evolution. The literature of course mentions corals in the Early Liassic for a long time in Western Europe (Orbigny, 1850; Martin, 1860; Dumortier, 1864; Fromentel and Ferry, 1865–1869; Duncan, 1865–1868; Terquem and Piette, 1868; Tomes, 1878, 1884a, 1888, 1893; Nicklès, 1902; Hahn, 1911; Joly, 1936). Part of these anciently known corals were revised by Alloiteau (1957) and Beauvais (1976) but new investigations have been undertaken more recently (Turnšek et al., 1975; Simms et al., 2002; Kiessling et al., 2009; Gretz et al., 2013, 2014; Gretz, 2014; Boivin et al., 2018). Early Jurassic corals have also been collected in Eastern Europe (Popa, 1981; Turnšek and Buser, 1999; Turnšek and Kosir, 2000; Turnšek et al., 2003), and a rather diverse fauna has been described from Central Asia (Melnikova, 1972, 1975a, 2006; Melnikova et al., 1993; Melnikova and Roniewicz, 2012, 2017) a part of which has been very recently reassigned to younger strata (Melnikova and Roniewicz, 2021).

Even if Lower Jurassic corals were also described from South America (Tilmann, 1917; Gerth, 1926, 1928; Wells, 1953; Prinz, 1991) and North America (Poulton, 1988; Stanley and McRoberts, 1993; Stanley and Beauvais, 1994; Hodges and Stanley, 2015), overall this is a difficult time for corals!

Africa has been poorly represented for a long and after some preliminary reports (Le Maître, 1935, 1937) the historical work of Beauvais (1986), devoted to the Liassic coral fauna of Morocco, appeared to be a keystone in our understanding of the group. However, the collection was mostly done in the Pliensbachian and Toarcian stages. Consequently, we undertook to revisit the field in Morocco taking advantage of the recent work of C. Durlet (unpublished), Sarih (2008) and Sarih et al. (2018) in the Amellagou region to investigate the Lower Jurassic successions.

Our recent fieldworks in Morocco, between 2014 and 2019, has already resulted in papers devoted to specific abundant taxa such as Hispaniastraea (Turnšek and Geyer, 1975; Boivin et al., 2019) and Neorylstonia Vasseur et al., 2019. This paper aims to establish a more complete record of early Liassic post-extinction corals. Following recent contributions involving European countries (Gretz et al., 2013, 2014; Boivin et al., 2018), the Moroccan outcrops in a favourable paleolatitudinal location offered a compelling opportunity to improve our knowledge of coral communities after the end-Triassic mass extinction.

2 Material and methods

A collection of coral specimens (157 samples) has been collected in the Amellagou region in the Moroccan High Atlas Mountains (Fig. 1). The material sampled is sourced from four Lower Jurassic outcrops presented in Table 1 and detailed below: the Dromedary biostrome (?Hettangian–Sinemurian), the Serdrar reef (upper Sinemurian), the Castle olistolith (upper Sinemurian or lowermost Pliensbachian) and the Owl olistolith (lower Pliensbachian).

|

Fig. 1 Map of the main structural domains of Morocco with location of Amellagou Region in High Atlas Mountains. Modified after Krencker et al. (2014). |

In the field, benthic macrofossils were collected extensively, to obtain a complete survey of each reef outcrop. Samples were extracted with a hammer and chisel as well as with a battery-powered angle grinder, when necessary. The material was then photographed and studied under a reflected light stereomicroscope (Wild M5A). They were then cut and polished to obtain thin transverse and longitudinal sections of 70 µm thickness, and of 24 by 36 mm or of 40 by 50 mm as appropriate.

The samples were numbered according to the following code: the initials “SB” (for Simon Boivin) followed by a number given directly in the field (e.g., SB–133). Each piece collected sample is identified by a unique number (i.e., no batch including several samples). Thin sections made from the samples are identified by a letter next to the sample number (e.g., SB–133-a). In many cases, different coral species are included in the same sample. To distinguish them, a number preceded by a slash has been added (e.g., the specimens SB–133/1 and SB–133/2).

The silicified corals were extracted with hydrochloric acid. As the matrix is calcareous and the silica is not affected by HCl, the samples were immersed in acid (30%). The corals are thus isolated without their matrix.

The samples were studied mainly from thin sections due to their preservation, which is often strongly eroded over their entire natural surfaces. The thin sections are studied and imaged using a polarised microscope and a thin-section scanner. The description of the coral specimens was carried out following the exhaustive list of observable coral characters proposed by Beauvais et al. (1993); a re-structured version is available in Bertling (1995).

In the aim to study the morphometry of coral specimens, several measurements were taken thanks to a calliper or under a microscope with calibrated measurement software depending on the dimensions of specimens. Table 2 presents the different measurements made, also shown in a schematic representation in Figure 2. Depending on the morphology, the colonial structure and the preservation of the material, not all measurements could be taken.

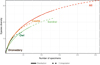

|

Fig. 2 Illustration of the main values measured for the morphometric study of corals. The black area corresponds to the skeleton. D calicular great diameter, d calicular small diameter, tw thickness of the wall, cc distance from corallite to corallite. |

The R software package was used to process the measurements and analyses (R Core Team, 2017) with the libraries ggplot2 (Wickham, 2009) for plots and iNext (Chao et al., 2014) for rarefaction curves. When sampling is large enough, the morphometric data were analysed with several Principal Component Analyses (PCA) with variance/covariance matrices. PAST software (Hammer et al., 2001) was also frequently used to visualize the data. All data are available in the appendices.

Presently, the samples are deposited at the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle of Geneva, Switzerland. In the future, they should be redeposited at the Direction de la Géologie, Ministère de l’Énergie, des Mines et du Développement Durable − Département de l’Énergie et des Mines (here abbreviated to DGR), in Rabat, Morocco.

Summary table of outcrops sampled in the Amellagou Region, High Atlas Mountains, Morocco.

Main measurements made on coral specimens.

3 Systematics & results

Taxonomic names and synonymies are formulated according to the conventions proposed by Matthews (1973) and open nomenclature is used according to Bengtson (1988). Thus, synonymies are commented on using the following signs placed before the binoma:

* with the publication of this work, the species can be regarded as available under the terms of Article 11 of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (1999).

we accept the responsibility of linking the species to this reference.

(no sign) we have no reason to doubt the attachment of the species to this reference.

? we consider the allocation of this reference must be subject to some doubt.

non we do not attach the species to this reference.

v for "Vidimus", means that we have checked the deposited specimens that relate to the cited work.

p the reference is only partially applicable to the species under discussion.

Year in italics the species is mentioned without description or illustration.

All the species are described below and presented in systematic order. A summary is available in Table 3 with the number of specimens per location and the colonial arrangement of each genus. The specimens reported in synonymies concerning (Boivin, 2019) are the same specimens described and illustrated here.

List of genera and species with their distribution by localities and colonial structures. The numbers correspond to the numbers of specimens and brackets to doubtful assignations.

3.1 Abbreviations of institutions used

BRLSI Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution, United Kingdom.

BSPG Bayerische Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und historische Geologie, Munich, Germany.

DGR Direction de la Géologie, Ministère de l’Energie, des Mines et du Développement Durable − Département de l’Energie et des Mines, Rabbat, Morocco.

MHNG Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle of Geneva, Switzerland.

MNHN Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France.

MSNP Museo di Storia Naturale dell’Università di Pisa, Calci, Italia.

Order Hexanthiniaria? Montanaro Gallitelli (1975)

Family Hispaniastraeidae (Boivin, Vasseur and Lathuilière (2019)

Genus Hispaniastraea Turnšek and Geyer (1975)

Type species. Hispaniastraea murciana Turnšek and Geyer (1975) by original designation.

Originally included species. Hispaniastraea murciana (Turnšek and Geyer, 1975) and Hispaniastraea ramosa (Turnšek and Geyer, 1975).

Etymology. Hispania from Spain in Latin.

Similarities and differences. The genus Hispaniastraea can be confused with the hypercalicified sponge genus Pseudoseptifer (Fischer, 1970) due to the similarities of their skeletons. A set of ten morphological features to distinguish these taxa is presented in Boivin et al. (2019).

Status. Available and valid

Hispaniastraea murciana Turnšek and Geyer (1975)

|

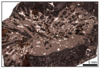

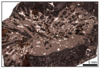

Fig. 3 Hispaniastraea murciana Turnšek & Geyer, 1975. A Natural transverse section of the specimen SB–243. B Transverse thin section of a branch of the specimen SB–246. C–D Longitudinal thin sections of branches of the specimen SB–246. |

|

Fig. 4 Hispaniastraea murciana Turnšek & Geyer, 1975. A Transverse thin section of a branch of the specimen SB–54. B Transverse thin section a branch of the specimen SB–85. C Longitudinal thin section of the specimen SB–169. D Longitudinal thin section of a branch of the specimen SB–53. |

* 1975 Hispaniastraea murciana sp. nov. — Turnšek & Geyer in Turnšek et al., p. 138, Pl. 20 figs. 1–2, Pl. 21 figs. 1–2.

1975 Hispaniastraea ramosa sp. nov. — Turnšek & Geyer in Turnšek et al., p. 139, Pl. 22 figs. 1–3.

? 1980 Chaetetes (Pseudoseptifer) murciana (Turnšek & Geyer) — Beauvais, p. 30, Pl. 3 fig 2.

v. 1980 Blastochaetetes dresnayi sp. nov. — Beauvais, p. 33–35, figs. 6–7, Pl. IV fig. 2.

? 1991 Hispaniastraea ramosa Turnšek & Geyer — Prinz, p. 167, Pl. 2 fig. 5.

? 1994 Hispaniastraea ramosa Turnšek & Geyer — Senowbari-Daryan & Stanley, p. 52–53, fig. 5, Pl. 1 figs. 4–8.

? 2003 Hispaniastraea ramosa Turnšek & Geyer — Turnšek et al., p. 292–293, Pl. 3 figs. 1–4.

v. 2018 Hispaniastraea murciana Turnšek & Geyer — Vasseur, p. 216–217, fig. 3 .46.

v. 2019 Hispaniastraea murciana Turnšek & Geyer — Boivin etal., p. 8–10, figs. 4–5.

v. 2019 Hispaniastraea murciana Turnšek & Geyer — Boivin, p. 212, figs. 10.14 and 10.15.

v. 2021 Hispaniastraea murciana — Vasseur and Lathuilière, p. 1231, fig. 29.

Type designation. Holotype by original designation, col. no. 33, Turnšek et al. (1975), p. 138.

Type locality and horizon. Upper Sinemurian − lower Pliensbachian from Zarcilla de Ramos, Province of Murcia, Spain.

Originally included material. Three colonies (33a, 33b and 34) and two fragments of colonies (35 and 36) from the same horizon as the holotype of the Seyfried collection, reposited at the Departamento de Paleontología of the University of Granada (UG), Spain.

Etymology. murciana from province of Murcia (Spain).

Material examined. 17 specimens: SB–53/1, SB–54, SB–55/4, SB–64/4, SB–85, SB–141, SB–145/2, SB–161/2, SB–163, SB–169/3, SB–233, SB–243, SB–246, SB–247, SB–315, SB–336 and SB–346/2.

Ages and localities of material. Upper Sinemurian from Serdrar reef, upper Sinemurian or lowermost Pliensbachian from Castle olistolith and lower Pliensbachian from Owl olistolith, Amellagou Region, High Atlas Mountains, Morocco.

Description. Colonies massive in shape or ramose, cerioid. Transverse section of corallites is sub-circular or polygonal. Septal apparatus characterized by one major septum highly dominant in length and thickness, and up to eleven minor septa. The major septum is straight or sometimes curved, compact, without ornamentation apart from the auriculae on the inner margin of the septum and reaches the centre of the lumen. Inner margin of the major septum is enlarged at the level of the auriculae and rounded otherwise, the lumen is typically horseshoe-shaped. Minor septa are very short, often not discernible on the surface of the inner wall, compact, and their outline in transverse section varies from triangular to semi-circular. Inner margins of the minor septa with sharp granules that alternate in height with the auriculae of the major septum. Corallites could be connected by canals. Endotheca made of thin tabulae rarely preserved.

Dimensions. Calicular great diameter 0.45 to 1.38 mm — Calicular small diameter 0.14 to 1 mm — Diameter of branches 10 to 15.78 mm — Distance from corallite to corallite 0.5 to 2.1 mm — Thickness of the wall 0.09 to 0.84 mm — Width of major septum (at its middle) 51 to 574 µm — Length of major septum 100 to 600 µm — Number of visible septa 1 to 12 septa.

Similarities and differences. Hispaniastraea murciana (Turnšek and Geyer, 1975) differs from Hispaniastraea ousriorum (Boivin, Vasseur and Lathuilière, 2019) that shows one to four well-developed S1 septa in addition to the major septum.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Sinemurian − lower Toarcian from Murcia (Spain), Middle and High Moroccan Atlas Mountains (Morocco), Languedoc (France), Calabria (Italia), as well as possibly North Chile and Peru, if the identifications of Prinz (1991) and Senowbari-Daryan and Stanley (1994) are confirmed.

Order Scleractinia (Bourne, 1900)

Family Actinastreidae (Alloiteau, 1952)

Genus Chondrocoenia (Roniewicz, 1989)

Type species. Prionastraea schafhaeutli (Winkler, 1861) by original designation.

Originally included species. Chondrocoenia schafhaeutli (Winkler, 1861), Chondrocoenia waltheri (Frech, 1890), Chondrocoenia ohmanni (Frech, 1890), Chondrocoenia sp. A and Chondrocoenia sp. B.

Similarities and differences. The genus Chondrocoenia differs from other Actinastreidae genera by its peritheca.

Etymology. Chondros a grain shaped object and koinos common from the granulated appearance of the coenosteum surface, both in ancient Greek.

Status. Available and valid.

Chondrocoenia clavellata (Terquem and Piette, 1865)

|

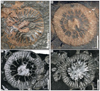

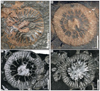

Fig. 5 Chondrocoenia clavellata (Terquem & Piette, 1865). A Specimen SB–194. B Enlargement of A. C Longitudinal thin section of branch of the specimen SB–49. D Enlargement of C. |

* 1865 Astrocoenia clavellata sp. nov. — Terquem & Piette, p. 130–131, Pl. 18 fig. 4–5.

1936 Astrocoenia clavellata Terquem & Piette — Joly, p. 172.

v. 2014 Chondrocoenia clavellata (Terquem & Piette) — Gretz, p. 99–102, Pl. 7–8.

v. 2018 Chondrocoenia clavellata (Terquem & Piette) — Boivin etal., fig. 3–c-d.

v. 2019 Chondrocoenia clavellata (Terquem & Piette) — Boivin, p. 188-189, fig. 10.2.

Type designation. Syntypes, no lectotype designated.

Type locality and horizon. Upper Hettangian − lower Sinemurian from Laval-Morency, Chilly, Maubert-Fontaine, Charleville and Saul, Northeastern France.

Originally included material. Unspecified. We did not localise the housing institution.

Etymology. From clava: club in Latin referring to the shape of branches.

Material examined. 3 specimens: SB–49, SB–194 and SB–318/2.

Ages and localities of material. Sinemurian from Dromedary biostrome and upper Sinemurian from Serdrar reef, Amellagou Region, High Atlas Mountains, Morocco.

Description. Ramose colonies, cerioid to plocoid. Transverse section of corallites sub-circular or polygonal. Radial elements are costosepta. Septa are thin, straight or curved, free or sometimes joined, confluent or sub-confluent, sub-compact. Septal apparatus ordered in two size orders. Lateral faces of septa are granulated. Inner margin of septa is rounded or slightly enlarged. Trabecular projections in the axial region. Columella styliform. Peritheca made of costae, dense, with granulated aspect in distal view of natural surface. Corallites inside branches are distributed in water-jet.

Dimensions. Calicular diameter 1 to 2 mm — Distance from corallite to corallite circa 0.9 to 1.7 mm — Septal density 6 to 8 septa per 1 mm.

Similarities and differences. See Chondrocenia martini below.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Hettangian − Sinemurian from France, Belgium and Morocco (High Atlas Mountains).

Chondrocoenia martini (Fromentel, 1860)

|

Fig. 6 Chondrocoenia martini (Fromentel, 1860). A Natural view of a calice of the specimen SB–343. B Transverse thin section of the specimen SB–343. C Enlargement of B. D Transverse thin section of the specimen SB–157. |

*v 1860 Stylastraea martini sp. nov. — Fromentel in Martin, p. 94, Pl. 7 fig. 18-19.

1861 Stylastraea martini Fromentel — Fromentel, p. 223.

1865 Stylastraea martini Fromentel — Terquem & Piette, p. 167.

1867 Astrocoenia plana sp. nov. — Duncan, p. 19, Pl. 5 fig. 1.

1867 Astrocoenia reptans sp. nov. — Duncan, p. 20, Pl. 4 figs. 4–5 and 15.

1867 Astrocoenia superba sp. nov. — Duncan, p. 21, Pl. 9 figs. 3–4.

1867 Cyathocoenia costata sp. nov. — Duncan, p. 29, Pl. 5 figs. 10–11.

1884b Stylastraea martini Fromentel — Tomes, p. 370.

1912 Stylastraea martini Fromentel — Lissajous, p. 179, pl. 18 fig. 54.

1917 Astrocoenia lissoni sp. nov. — Tilmann, p. 701, Pl. 26 fig. 4.

? 1953 Astrocoenia sp. cf. lissoni Tilmann —Wells, p. 3, fig. 1.

1976 Actinastraea plana (Duncan) — Beauvais, p. 44, Pl. 8 figs. 1–4, text-figs. 1–2.

1991 Actinastrea plana (Duncan) — Prinz, p. 161, Pl. 1 fig. 11.

1994 Actinastraea plana (Duncan) — Stanley & Beauvais, p. 43.

2013 Stylastraea martini Fromentel — Lathuilière, www.corallosphere.org with figures.

v. 2019 Chondrocoenia plana (Duncan) — Boivin, p. 190-191, fig. 10.3.

Type designation. Syntype. MHNG GEPI 036087.

Type locality and horizon. Hettangian (initially described in the Ammonites moreanus zone), from Vic de Chassenay, Côte d’Or, France.

Originally included material. Unspecified.

Etymology. Dedicated to Jules Martin.

Material examined. 2 specimens: SB–157 and SB–243.

Ages and localities of material. Upper Sinemurian or lowermost Pliensbachian from Castle olistolith and lower Pliensbachian from Owl olistolith, Amellagou Region, High Atlas Mountains, Morocco.

Description. Colonies cerioid to plocoid. Massive in shape. Transverse section of corallite circular to sub-circular. Septa are thick, straight, free or joined, compact, non-confluent. Septal apparatus organized in two size orders, typically eight to twelve S1 and a variable number of S2. S2 septa are thinner than S1 septa. Septal junctions are very regular: S2 septa are joined to neighbouring S1 septa. Lateral faces of S1 and S2 septa are ornamented with granules. Septa are enlarged at outer margin that give to corallite a multi-lobed aspect. Columella styliform. Extra-calicular budding. Radial symmetry very marked in smaller corallites. Endotheca made of dissepiments.

Dimensions. Calicular diameter 0.9 to 3.45 mm — Distance from corallite to corallite 2 to 3 mm — Septal density 3 to 4 septa per 1 mm — Number of septa circa 20 septa.

Similarities and differences. This species is close from Chondrocoenia clavellata (Terquem and Piette, 1865) but differs by its lower septal density and the colonial form.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Hettangian from Chile and Great Britain, Sinemurian from Canada, Sinemurian − Pliensbachian from Morocco (High Atlas Mountains), Middle Liassic of Peru.

Genus Lochmaeosmilia (Wells, 1943)

Type species. Stylosmilia trapeziformis (Gregory, 1900) by original designation.

Originally included species. Lochmaeosmilia aethiopica (Wells, 1943), Lochmaeosmilia koniakensis (Ogilvie, 1897) and Lochmaeosmilia trapeziformis (Gregory, 1900).

Similarities and differences. The genus Lochmaeosmilia is characterised by its interconnecting apophyses, a character that is known in another genus i.e., Apocladophyllia (Morycowa and Roniewicz, 1990), a coral known in Toarcian (Vasseur et al., 2021) and in the interval Kimmeridgian-Berriasian. According to Morycowa and Roniewicz (1990), the septal apparatus is regular radial and bi-radial in Apocladophyllia, and particularly irregular and anastomosing in Lochmaeosmilia. The microstructure is said to be different due to minute and dense granules in Apocladophyllia that have not been observed in Lochmaeosmilia.

Etymology. From lochme: thicket, copse, especially as the lair of wild beast, in ancient Greek referring to the branching form of the colony, and smilia: scalpel biter also in ancient Greek.

Status. Available and valid.

Lochmaeosmilia? sp.

|

Fig. 7 Lochmaeosmilia? sp. Transverse thin section of the specimen SB–155. |

Material examined. 1 colony: SB–155.

Ages and localities of material. Upper Sinemurian or lowermost Pliensbachian from Castle olistolith, Amellagou Region, High Atlas Mountains, Morocco.

Description. Branching colony with high density of calices, extensively recrystallised. Septal apparatus almost not visible (Fig. 7). Branches are regularly connected witch each other by apophyses.

Dimensions. Diameter of corallites 0.3 mm — 3 to 4 branches per mm2 — Number of septa: 12 (approximated from a quarter of calix) — Septal density: 2 septa per 100 µm.

Remarks. The preservation of our single specimen does not allow a formal identification, despite it is probably a new species. The diagnostic characters of the septa were not observed, that is why we put a question mark after the genus name.

Similarities and differences. Our specimen can be distinguished from other nominal species of Lochmaeosmilia by the low size of its corallites (Tab. 4). This is also valid for species of Apocladophyllia (Tab. 4).

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Sinemurian − lowermost Pliensbachian from Morocco (High Atlas Mountains). The extension of the genus which was considered Middle Jurassic in age (Beauvais, 1971), is probably much wider.

FamilyAstraeomorphidae (Frech, 1890)

Genus Parastraeomorpha (Roniewicz, 1989)

Type species. Parastraeomorpha minuscula (Roniewicz, 1989) by original designation.

Originally included species. P. minuscula (Roniewicz, 1989) and P. similis (Roniewicz, 1989).

Similarities and differences. This genus is close to Astraeomorpha (Reuss, 1854) but differs by the lack of menianae and the development of thick synapticulae with oblique axes whereas they are horizontal in Parastraeomorpha.

Etymology. From para: near in ancient Greek, referring to the morphological similarity to Astraeomorpha (Reuss, 1854).

Status. Available and valid.

Parastraeomorpha minuscula (Roniewicz, 1989)

|

Fig. 8 Parastraeomorpha minuscula Roniewicz, 1989. A Transverse thin section of the specimen SB–344. B–C–D Enlargement of A. |

p 1890 Astraeomorpha confusa Winkler. var. nov. minor — Frech, p. 68, Pl. 19 figs. 4, 11 and 12 (non fig. 1, nec 7).

* 1989 Parastraeomorpha minuscula sp. nov. — Roniewicz, p. 98-99, Pl. 30 figs. 1–2.

2003 Parastraeomorpha minuscula Roniewicz — Stanley & Yarnell, p.114.

v. 2019 Parastraeomorpha minuscula Roniewicz — Boivin, p. 230-231, fig. 10.22.

Type designation. Holotype by original designation, NHMW 1982/57/17, (Roniewicz, 1989): p.98, Pl. 30 fig. 1.

Type locality and horizon. Rhaetian from Zlambach Beds of Fischerwiese, Northern Calcareous Alps, Austria.

Originally included material. Twenty-five fragments of colonies and four thin-sections.

Etymology. From minuscula: small in Latin referring to the small corallite dimensions.

Material examined. 1 colony: SB–344.

Ages and localities of material. Lower Pliensbachian from Owl olistolith, Amellagou Region, High Atlas Mountains, Morocco.

Description. Colony thamnasterioid with some aphroid tendencies, columnar. Corallites densely distributed without apparent organisation. Radial elements are bisepta or septa, confluent or not confluent, compact, often joined, flexuous. Septal apparatus hierarchized in two size orders. S1 septa are long and reach the columella, whereas S2 septa are joined to neighbouring S1 septa. Lateral faces of septa are ornamented with probable pennulae (the only available sections are not favourable for this observation). Symmetry hexameral well regular, indicating an intercalicular budding. Synapticula present. Axial area is occupied by a columella of unknown nature (perhaps parietal) and extremity of S1 septa. No wall.

Dimensions. Size of colony 9.4 × 11.3 mm — Calicular diameter circa 1 mm — Distance from corallite to corallite 0.9 to 1.2 mm — Number of septa circa 12–15 septa.

Similarities and differences. This species differs from Parastraeomorpha similis (Roniewicz, 1989) that has larger diameter of corallites, robust skeletal elements and a lamellar colony growth form.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Rhaetian from Austria (Northern Calcareous Alps), Upper Triassic from Alaska, Pliensbachian from Morocco (High Atlas Mountains).

Family Comoseriidae (Fromentel, 1861) (= Microsolenidae Koby, 1889)

Genus Eocomoseris (Melnikova, Roniewicz and Löser, 1993)

Type species. Eocomoseris gurumdyensis nomen novum pro Eocomoseris ramosa Melnikova, 1993 non (Frech, 1890), p. 5, Pl. I fig. 1–3 by original designation. The type species is now considered to be junior synonym of Eocomoseris minima (Beauvais, 1986) by Vasseur and Lathuilière (2021, p. 1203).

Originally included species. Eocomoseris gurumdyensis Melnikova, 1993, Eocomoseris lamellata Melnikova, 1993, Eocomoseris raueni Loeser, 1993.

Similarities and differences. This genus seems very close to Spongiomorpha (Frech, 1890) that was placed among the Astraeomorphidae (Frech, 1890) (Roniewicz, 2010a). The connection between Astraeomorphidae and Comoseriidae remains a matter for future researches.

Etymology. Eos from dawn in ancient Greek and Comoseris referring to the comoseriid phylogeny.

Status. Available and valid.

Eocomoseris minima (Beauvais, 1986)

|

Fig. 9 Eocomoseris minima (Beauvais, 1986). A Longitudinal thin section of a branch of the specimen SB–222. B Enlargement of A. C Transverse thin section of branches of the specimen SB–245. D–E Enlargement of C. F Longitudinal thin sections of branches of the specimen SB–245. |

|

Fig. 10 Eocomoseris minima (Beauvais, 1986). A Longitudinal thin section of the specimen SB–167/2. B Longitudinal thin section of the specimen SB–316/2. |

P 1982 Actinastrea minima nomen nudum — Beauvais, p. 1964, pl. 1, fig. 3.

* 1986 Actinastrea minima sp. nov. — Beauvais, p. 31, Pl. 2 fig. 6, Pl. 6 fig. 6.

1993 Eocomoseris ramosa sp. nov. — Melnikova, p. 5, pl. I fig 1–3.

? 1994 Actinastraea minima Beauvais — Stanley & Beauvais, p. 42, fig. 6a–c (non fig. 6d).

2011 Eocomoseris gurumdyensis nomen novum pro Eocomoseris ramosa Melnikova — Roniewicz, p. 422.

2011 Eocomoseris ramosa (Frech, 1890) — Roniewicz, p. 424, fig. 7F.

v. 2019 Eocomoseris? cf. minima (Beauvais) — Boivin, p. 202-203, fig. 10.9–10.12.

2021 Eocomoseris gurumdyensis Melnikova in Roniewicz — Melnikova & Roniewicz, Table 1.

2021 Eocomoseris minima (Beauvais) — Vasseur & Lathuilière, p. 1203, fig. 9.

Remarks. Beauvais (1982) described under the name Actinastrea minima one specimen from Canada and designated another Moroccan specimen as a holotype, subsequently described in Beauvais (1986). The Canadian specimen is explicitly referred to a nomen nudum and the name has been available since 1986 (Articles 11 and 13 of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature). We assign our material to the species defined by the Moroccan holotype (designated in (Beauvais, 1982) and described in (Beauvais, 1986) but we have reservation about the Canadian specimen that looks like a real actinastreid.

Type designation. Holotype MNHN.F.R11620, by original designation (Beauvais 1986, cf. remark above).

Type locality and horizon. Domerian from Jebel Bou Dahar, High Atlas Mountains, Morocco.

Originally included material. 9 specimens from the collection Menchikoff.

Etymology. minima from the small diameter of corallites.

Material examined. 16 specimens: SB–53/2, SB–64/1, SB–144/1, SB–146/2, SB–169/1, SB–198, SB–219/1, SB–222, SB–235, SB–245, SB–313, SB–317, SB–323 and SB–334.

Ages and localities of material. Upper Sinemurian from Serdrar reef, upper Sinemurian or lowermost Pliensbachian from Castle olistolith, and lower Pliensbachian from Owl olistolith, Amellagou Region, High Atlas Mountains, Morocco.

Description. Ramose colonies, branching or massive, thamnasterioid. Corallite small, vaguely delimited. Septa perforate, straight or curved, confluent. Septal apparatus organised in one size order. Septa are joined by two at their inner margin. Septa trabecular with pennulae, alternating with those of neighbouring septa. Columella styliform perhaps mono-trabecular (Fig. 9A). Synapticulae present.

Dimensions. Calicular diameter 1 to 2 mm — Diameter of branches 5 to 15 mm — Septal density 6 to 11 septa per 2 mm — Distance from corallite to corallite 1.2 to 1.8 mm — Width of pennulae circa 100 to 140 µm.

Similarities and differences. Eocomoseris minima differs from:

— Eocomoseris lamellata Melnikova, 1993 by its lamellar shape and well delimited corallites.

— Eocomoseris raueni Loeser, 1993 by its massive globular or flat shape and its larger corallites (Calicular diameter 2 to 3 mm and Distance from corallite to corallite 1.5 to 3.5 mm, according Melnikova et al., 1993).

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Norian from Austria, Sinemurian from Canada? Sinemurian − Pliensbachian from Morocco, Pliensbachian from Tajikistan.

Family Conophylliidae (Alloiteau, 1952)

Genus Araiophyllum (Cuif, 1975b)

Type species. Araiophyllum triasicum (Cuif, 1975b), p. 110–115, Pl. 16, figs. 17 and 18, by monotypy.

Originally included species. Only the type species.

Similarities and differences. This genus is close to genera Eocomoseris (Melnikova, Roniewicz and Löser, 1993) and Spongiomorpha (Frech, 1890) by its perforated nature, but it differs by its phaceloid nature.

Etymology. From araios: porous and phyllum: leaf, both in ancient Greek.

Status. Available and valid.

Araiophyllum triasicum (Cuif, 1975b)

|

Fig. 11 Araiophyllum triasicum (Cuif, 1975b). Transverse thin section of the specimen SB–242/2. |

* 1975b Araiophyllum triasicum sp. nov. — Cuif, p. 110–115, p. 126, figs. 17–18, Pl. 16.

1989 Araiophyllum cf. triasicum Cuif — Turnšek & Buser, p. 86, Pl. 7 figs. 1–2.

1993 Araiophyllum triasicum Cuif — Cuif & Gautret, p. 407–408, Pl. 1 figs. 1–4.

1997 Araiophyllum triasicum Cuif — Turnšek, no 20.

v. 2019 Araiophyllum triasicum Cuif — Boivin, p. 186-187, fig. 10.1.

Type designation. Holotype by original designation (p. 115), MNHN.F.A79197.

Type locality and horizon. Carnian from Taurus Mountains, Lycia, Anatolia, Alakir Cay valley.

Originally included material. The text is ambiguous. Perhaps only one.

Etymology. From Triassic referring to the stratigraphic position of the material.

Material examined. 1 specimen: SB–242/2.

Ages and localities of material. Lower Pliensbachian from Owl olistolith, Amellagou Region, High Atlas Mountains, Morocco.

Description. Detached branch of a phaceloid coral. Radial elements are septa with pennulae without meniana, perforate, straight or slightly sinuous, joined. Septal apparatus organised in two size orders. S1 reach the papillose columella. S2 septa are short, sometimes contratingent on neighbouring S1 septa. Endotheca badly preserved, perhaps made of dissepiments. Perhaps pellicular epitheca.

Dimensions. Calicular great diameter 4.8 mm — Calicular small diameter 3.9 mm — Thickness of the wall circa 0.2 to 0.5 mm — Number of septa 25 or 26 septa — Septal density 3 to 4 septa per 1 mm.

Similarities and differences. Araiophyllum triasicum (Cuif, 1975b) differs from Araiophyllum liassicum (Beauvais, 1986) which has calices with a higher diameter (4 to 12 mm) and a greater septal density (12 septa per 2 mm).

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Carnian from Turkey (Taurus Mountains) and Slovenia (Pokljuka), Pliensbachian from Morocco (High Atlas Mountains).

Genus Thecactinastraea (Beauvais, 1986)

Type species. Thecactinastraea fasciculata (Beauvais, 1986) by original designation.

Originally included species. Only the type species.

Remarks. Thecactinastraea (Beauvais, 1986) and Phacelophyllia (Beauvais, 1986) are considered synonyms. In accordance with the principle of the first reviser (ICZN Art. 24.2) the priority is given to Thecactinastraea because the first synonymy was proposed in Melnikova and Roniewicz (2017), and not in Brame et al. (2019).

Similarities and differences. This genus differs from the phaceloid genera:

Paracuifia (Melnikova, 2001) that has poorly ornamented septa.

Paravolzeia (Roniewicz et al., 2005) that has poorly ornamented septa too.

Phacelostylophyllum (Melnikova, 1972) that is stylophyllid in septal structure.

Retiophyllia (Cuif, 1966) that is a distichophylliid in structure and shows a typical epitheca.

Etymology. From the genera Thecosmilia referring to the external morphology and Actinastraea referring to the structure of radial elements according to (Beauvais (1986).

Status. Available and valid.

Thecactinastraea fasciculata (Beauvais, 1986)

|

Fig. 12 Thecactinastraea fasciculata Beauvais, 1986. A–C Transverse thin sections of the specimen SB–153. D Oblique thin section of the specimen SB–80. E Enlargement of D. F Oblique thin section of the specimen SB–80. |

* 1986 Thecactinastraea fasciculata sp. nov. —Beauvais, p.33, Pl. 5 fig. 1, text-fig. 21.

1986 Myriophyllum fasciatum sp. nov. — Beauvais, p.37, Pl. 9 fig. 1, text-fig. 25.

non 2003 Thecactinastraea fasciculata Beauvais — Turnšek et al., p.293, Pl.4 fig. 1-5.

2003 Phacelophyllia fasciata (Beauvais) — Turnšek et al., p.297, Pl.9 fig. 4.

2017 Thecactinastraea fasciculata Beauvais — Melnikova & Roniewicz, p. 133, fig. 3C, D.

v. 2018 Phacelophyllia fasciculata (Beauvais) — Vasseur, p. 279, fig. 3

v. 2019 Phacelophyllia fasciculata (Beauvais) — Boivin, p. 240, fig. 10

Remarks. Thecactinastraea fasciculata in Turnšek et al. (2003) is excluded of our synonymy because of the difference in the septal microstructure and microarchitecture similar to Cuifiidae (Melnikova, 1975b). Prinz (1991) considered Thecosmilia suttonensis (Duncan, 1867) to be a senior synonym of T. fasciculata Beauvais. We rather assign the Duncan’s species to the stylophyllid genus Phacelostylophyllum.

Type designation. Holotype by original designation, MNHN.F.R11611.

Type locality and horizon. Lower Jurassic from Tarhilest, near of Dayet Ifrah, Morocco.

Originally included material. 4 specimens from the collection du Dresnay, no. 4975 (1 specimen) and 4569 bis (3 specimens).

Etymology. From fasciculata: fasciculate in Latin.

Material examined. 2 colonies: SB–80 and SB–153.

Ages and localities of material. Upper Sinemurian or lowermost Pliensbachian from Castle olistolith, Amellagou Region, High Atlas Mountains, Morocco.

Description. Phaceloid colonies with a high density of branches. Transverse section of corallites sub-circular or deformed by the intracalicular budding. Radial elements are septa sub-compact, free, straight or slightly curved. Septal apparatus organised in three size orders hierarchized in length and thickness. S3 septa are very short and are not always visible (Fig. 12A). Septa pennular. Septa of all size orders show numerous trabecular detachments near the inner edge. Elongated fossa inducing a bilateral symmetry. Endotheca made of dissepiments. Peripheral wall.

Dimensions. Calicular great diameter 4.8 to 8.2 mm — Calicular small diameter 4.2 to 6.1 mm — Septal density 4 to 6 septa per 2 mm.

Similarities and differences. See T. termierorum (Beauvais, 1986) below.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Upper Sinemurian − Toarcian from Morocco (Middle and High Atlas Mountains), Pliensbachian from Afghanistan, Domerian from Slovenia.

Thecactinastraea termierorum (Beauvais, 1986)

Figures 13 and 14

|

Fig. 13 Thecactinastraea termierorum (Beauvais, 1986). A–B Transverse thin section of the specimen SB–379. C Longitudinal thin section of the specimen SB–200. D–E Longitudinal thin section of the specimen SB–55/3. F Transverse thin section of the specimen SB–55/3. |

|

Fig. 14 Thecactinastraea termierorum (Beauvais, 1986). A–D Transverse thin sections of branches of the specimen SB–62. |

* 1986 Phacelophyllia termieri sp. nov. — Beauvais, p. 39, Pl. 7 fig. 2, text-fig. 27.

2003 Phacelophyllia termieri Beauvais — Turnšek et al., p. 297, Pl. 9 figs. 1–3.

2018 Phacelophyllia termieri Beauvais — Vasseur, p. 284-285, fig. 3.73.

v. 2019 Phacelophyllia termieri Beauvais — Boivin, p. 244, figs. 10.26–10.27.

Type designation. Holotype by original designation, MNHN.F.R11621.

Type locality and horizon. Lower Jurassic from Morocco (precise location unknown).

Originally included material. Only the holotype.

Etymology. Dedicated to Geneviève and Henri Termier. That is the reason why we emend the species name into a genitive plural (according to Articles 31.1.2 and 32.5 of the ICZN).

Material examined. 4 colonies: SB–55/3, SB–62, SB–200 and SB–379.

Ages and localities of material. Upper Sinemurian from Serdrar reef, Amellagou Region, High Atlas Mountains, Morocco.

Description. Colonies phaceloid with subparallel branches. Transverse section of corallites sub-circular or deformed by the intracalicular budding. Radial elements are septa sub-compact, joined, straight or curved. Septal apparatus organised in two or three size orders hierarchized in length but not in thickness. S1 septa are generally joined at their inner margins and reached the axial region. S2 septa are limited in length by the junction of the two neighbouring S1 septa. S3 septa are very short and are not always visible. Septa pennular. Few septa show trabecular detachments projecting into the axial region. Columella papillose. Epitheca made of dissepiments that can sometimes correspond on both side of a septum.

Dimensions. Calicular great diameter 5.9 to 7.7 mm — Calicular small diameter 4.5 to 7 mm — Septal density 5 to 8 septa per 2 mm. — Number of septa: 42 to 64 septa.

Similarities and differences. This species differs from Thecactinastraea fasciculata (Beauvais, 1986) that shows free septa and more trabecular detachments at inner margins of septa. P. termierorum differs from P. bacari (Turnšek, 2003) by the lower number of its septa and the higher size of its corallites.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Lower Jurassic from Morocco, Upper Sinemurian from Morocco (High Atlas Mountains), Domerian from Slovenia, Toarcian from Morocco (High Atlas Mountains).

Family Cuifiidae (Melnikova, 1975b) (= Coryphyllidae Beauvais, 1981)

Remark on the family name. Melnikova (1975b) created the family Cuifiidae with Cuifia as a type genus and Cuifia gigantella as the type species of the type genus. Cuif (1975a) created the genus Coryphyllia, which he subsequently placed within his new family Distichophyllidae in Cuif (1977). Beauvais (1981) created a new family Coryphyllidae with Coryphyllia as a type genus. Roniewicz (1989) used the latter family erected by Beauvais but as a subfamily (Coryphyllinae) including it within Reimaniphyllidae (Melnikova 1975) (senior synonym of Distichophyllidae). However, Roniewicz and Stanley (2009) redrew the boundaries of the Coryphylliidae to include both Cuifia and Coryphyllia. This nomenclatural act that contradicts the principle of priority was subsequently followed by various authors (Roniewicz 2010c, Bo et al., 2017, Mannani 2020, Vasseur et al., 2021, Vasseur and Lathuilière 2021). Then we re-establish here the priority of Cuifiidae over Coryphylliidae.

Genus Coryphyllia (Cuif, 1975a)

Type species. Coryphyllia regularis (Cuif, 1975b) by original designation.

Originally included species. Only the type species.

Similarities and differences. Coryphyllia differs from:

- Cuifia (Melnikova, 1975b) by the structure of wall, epithecal in Coryphyllia whereas Cuifia shows a peculiar segmented structure of wall. In absence of microstructure preserved, these two genera are distinguished here by the differences of size orders (6 in Cuifia) and the number of septa (between 120–160 septa and septal density of 3–5 septa per 1 mm in Cuifia).

- Distichophyllia (Cuif, 1975c) that is characterised by a mid-septal line in zigzag, which is expressed in the morphology of thin septa. Moreover, Distichophyllia shows a septal apparatus hierarchized in thick S1 and S2 septa whereas following size orders septa are thin.

- Stylophyllopsis (Frech, 1890) that is characterised by septal spines joined by stereome, often producing detachments at the inner edge and a festooned transverse section in more outer position. The mid-septal line is very rare in Stylophyllopsis. The elongation of the fossa is also a good character for Coryphyllia.

Etymology. From coryphe: crest and phyllia: leaf both in ancient Greek.

Status. Available and valid.

Coryphyllia capillaria (Vasseur and Lathuilière, 2021)

|

Fig. 15 Coryphyllia capillaria Vasseur & Lathuilière, 2021. A Transverse thin section of the specimen SB–244. B–C Longitudinal thin section of the specimen SB–230/1, section B distal and section C proximal. D Longitudinal thin section of the specimen SB–214. E Transverse thin section of the specimen SB–214. F Enlargement of E. Note the mid-septal line. |

v. 2018 Coryphyllia sp. 1 — Vasseur, p. 152-153, fig. 3.19.

v. 2019 Coryphyllia capillaria Vasseur & Lathuilière — Boivin, p. 192, fig. 10.4.

*v. 2021 Coryphyllia capillaria sp. nov. — Vasseur & Lathuilière, p. 1211, fig. 15.

Type designation. Holotype by original designation, CPUN PFPyr 7-2 in (Vasseur and Lathuilière 2021), the name was not available in Boivin (2019) ICZN art. 8.3.

Type locality and horizon. Pliensbachian from Estivère Pass, French Pyrenees.

Originally included material. Eight paratypes: CPUN 2303A1-2, CPUN 2303A8-1, CPUN AM16183-4, CPUN CDAm7, CPUN MA0504E7-13, CPUN MA0504E7-17, CPUN MA0704E3-10, CPUN MA0704E3-12.

Etymology. From capillus: hair in Latin referring to the very thin and long septa of high orders.

Material examined. 6 specimens: SB–230/1, SB–223, SB–244, SB–249, SB–341 and SB–346/1, and 1 uncertain silicified specimen: SB–68.

Ages and localities of material. Upper Sinemurian from Serdrar reef and lower Pliensbachian from Owl olistolith, Amellagou Region, High Atlas Mountains, Morocco.

Description. Solitary coral, conical, transverse section of corallite subcircular to slightly elliptical. Costosepta organised in a regular septal apparatus of three or four size orders difficult to distinguish. Septa are mostly straight or curved according to the bilateral symmetry, compact, free, slightly attenuated at inner margin. Lateral faces are weakly granulated. Endotheca made of abundant vesicular dissepiments regularly distributed in the interseptal space. Elongated fossa.

Dimensions. Calicular diameter 25 to 33 mm — Septal density 4 to 12 septa per 5 mm.

Similarities and differences. See C. regularis below.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Sinemurian — Pliensbachian from Morocco (Middle and High Atlas Mountains), Pliensbachian from France (Pyrenees).

Coryphyllia regularis (Cuif, 1975a)

|

Fig. 16 Coryphyllia regularis Cuif, 1975a. A Transverse thin section of the specimen SB–69. B Transverse thin section of the specimen SB–146/1. C Transverse thin section of the specimen SB–316/1. D Transverse thin section of the specimen SB–242/1. |

* 1975a Coryphyllia regularis sp. nov. — Cuif, p. 380, fig 37 a–c, fig. 38.

1984 Coryphyllia regularis Cuif — Ramovš & Turnšek, p. 175, Pl. 4 fig. 1.

1989 Coryphyllia regularis Cuif — Turnšek & Buser, p. 84, Pl. 3.

1994 Coryphyllia regularis Cuif — Turnšek & Senowbari-Daryan, p. 481, Pl. 3 fig. 5.

2013 Coryphyllia regularis Cuif — Liao & Deng p. 54, Pl. 20 fig. 4.

v. 2018 Coryphyllia regularis Cuif — Vasseur, p. 194-195, fig. 10.5.

v. 2019 Coryphyllia regularis Cuif — Boivin, p. 194–195, figs. 10.5.

v. 2021 Coryphyllia regularis Cuif — Vasseur & Lathuilière, p. 1214, fig. 16.

Type designation. Holotype by original designation. MNHN.F.A31946; (Cuif, 1975a): p. 379, fig. 37 a, b? and c?

Type locality and horizon. Lower Norian from Valley Alakir Cay, Taurus Mountains, Turkey.

Originally included material. Cuif (1975a) specified that several specimens are included in the species but no further detail is given.

Etymology. From regularis in Latin referring to the regularity of the septal apparatus.

Material examined. 5 specimens: SB–69, SB–140, SB–146/1, SB–242/1 and SB–316/1 and 3 uncertain specimens: SB–145/1, SB–248 and SB–251.

Ages and localities of material. Upper Sinemurian from Serdrar reef, upper Sinemurian or lowermost Pliensbachian from Castle olistolith and lower Pliensbachian from Owl olistolith, Amellagou Region, High Atlas Mountains, Morocco.

Description. Solitary coral, transverse section of corallite circular to elliptical. Radial elements are septa (costae not visible) organised in a regular septal apparatus of three size orders. Septa are straight or curved, compact, free, sometimes contratingent, attenuated at inner margin, often rhopaloid. Lateral faces are ornamented with granules of low relief. Inner margin of septa is smooth. Vestiges of a wavy mid-septal line often visible. Columella absent, the fossa is tight and elongated (notably in elliptical corallite), defining the apparent bilateral symmetry of the corallite. Endotheca typical for this species, made of abundant vesicular dissepiments regularly distributed in the interseptal space.

Dimensions. Calicular great diameter 14.5 to 40 mm — Calicular small diameter 12.75 to 38 mm — Septal density 3 to 8 septa per 5 mm.

Similarities and differences. Coryphyllia regularis differs from:

- Coryphyllia capillaria (Vasseur and Lathuilière, 2021) by its lower number of septa, its lower septal density, and the size orders of its septal apparatus better hierarchized.

- Coryphyllia subregularis (Beauvais, 1986) that shows equivalent dimensions, differs by a less regular septal apparatus and larger dissepiments, and possibly a lacking epitheca.

- Coryphyllia bicuneiformis (Melnikova 1975 Vasseur and Lathuilière, 2021 Vasseur and Lathuilière, 2021) has a smaller diameter, more bicuneiform septa and a more elongated calice.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Upper Triassic from China, Greece, Turkey and Slovenia, Sinemurian and Pliensbachian from Morocco (Middle and High Atlas Mountains).

Coryphyllia subregularis ? (Beauvais, 1986)

|

Fig. 17 Coryphyllia subregularis ? Beauvais, 1986. Oblique thin section of the specimen SB–169/2. |

?p Stylophyllopsis mojsvari sp. nov. — (Frech, 1890), p. 52, Pl. 10 figs. 7—8, non figs. 9—14.

* 1986 Coryphyllia subregularis sp. nov. — Beauvais, p. 23, Pl. 4 fig. 3.

v. 2018 Coryphyllia subregularis Beauvais — Vasseur, p. 156–157, fig. 3.21.

v. 2019 Coryphyllia subregularis Beauvais — Boivin, p. 196, figs. 10.6.

2021 Coryphyllia subregularis Beauvais — Vasseur & Lathuilière, p. 1214, fig. 17.

Type designation. Holotype by original designation MNHN.F.R11609; Beauvais, p. 23, Pl. 4, fig. 3.

Type locality and horizon. Domerian, Fuciniceras cornacaldense horizon, from Jebel el Kounif (Bou-Arfa Range), Morocco.

Originally included material. No mentioned material other than the holotype.

Etymology. From sub: close to in Latin referring to the proximity with the species C. regularis.

Material examined. 1 uncertain specimen: SB–169/2.

Ages and localities of material. Upper Sinemurian or lowermost Pliensbachian from Castle olistolith, High Atlas Mountains, Morocco.

Description. Solitary coral. Septal apparatus regular. Septa are straight or curved, compact, sometimes contratingent, often rhopaloid. Endotheca made of large vesicular dissepiments regularly distributed in the interseptal space.

Dimensions. Septal density 4-5 septa per 5 mm.

Similarities and differences. This species is close to Coryphyllia regularis (Cuif, 1975a) and shows equivalent dimensions, but differs by a less regular septal apparatus and larger dissepiments. For comparison with other species, see C. regularis.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Rhaetian from Austria? Upper Sinemurian − Pliensbachian from Morocco Middle and High Atlas Mountains.

Genus Paracuifia (Melnikova, 2001)

Type species. Protoheterastraea magnifica (Melnikova, 1984) by original designation, p. 44.

Originally included species. Paracuifia magnifica (Melnikova, 1984) and Paracuifia tortuosa (Melnikova, 2001).

Similarities and differences. Paracuifia is the single genus of Cuifiidae that shows phaceloid colonies. For comparisons with similar genera, see genus Thecactinastraea.

Etymology. From para: nearly in ancient Greek and cuifia referring to the genus Cuifia.

Status. Available and valid.

Paracuifia castellum sp. nov.

|

Fig. 18 Paracuifia castellum sp. nov. A & E transverse section of branches of the holotype SB–78/1. B–D longitudinal section of branches of the holotype SB–78/1. F Enlargement of E. |

Type designation. Holotype designated herein: SB–78/1 (20 thin sections: SB–78A to SB-78F, SB–78H to SB-78U).

Type locality and horizon. Upper Sinemurian or lowermost Pliensbachian from Castle olistolith, Amellagou Region, High Atlas Mountains, Morocco.

Originally included material. Only the holotype.

Etymology. From castellum: castle in Latin referring to the Castle olistolith named after the Berber ruins located just above the reef.

Diagnosis. Paracuifia with circular or slightly subcircular corallite about one centimetre in diameter, and around thirty septa.

Description. Colony phaceloid. Corallite circular or slightly subcircular. Septa thick, compact along the entire length, free or joined, straight or slightly undulated. Septal apparatus ordered in two size orders. Lateral margin of septa without ornamentation. Ghost of microstructure characterised by an aligned set of brown dots in the mid septal plan (Fig. 18F). Mid-septal line straight to slightly wavy (Fig. 18E). Endotheca made of large dissepiments regularly distributed in the interseptal space. These dissepiments show the same microstructure as septa (Fig. 18B), which indicated that the septa would be mostly made of thickening deposits. Columella absent. Costae absent. Probably trabeculothecal wall (Fig. 18E).

Dimensions. Calicular diameter 9.2 to 11.5 mm — Number of septa 30 septa — Septal density 2 to 3 septa per 3 mm.

Similarities and differences. Paracuifia castellum sp. nov. differs from:

— Paracuifia magnifica (Melnikova, 1984) that has an elliptic shape of corallites, a diameter from 6 mm in juvenile stage to 40 mm, and a number of septa around 200 in 5 size orders in adult stage.

— Paracuifia tortuosa (Melnikova, 2001) that has an elliptic shape of corallites, a diameter from 8 to 40 mm, and 130 to 150 septa in four size orders.

— Paracuifia smithi (Caruthers and Stanley, 2008) that has a very large and irregular corallite, a diameter from 10 to 23 mm, a tendency to be pseudo-meandroid, and poorly developed S2 septa.

— Paracuifia jennieae (Caruthers and Stanley, 2008) that has a pseudo-meandroid arrangement and a septal apparatus organised in four size orders.

— Paracuifia anomala (Caruthers and Stanley, 2008) that shows a cerioid arrangement of corallites.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Upper Sinemurian or lowermost Pliensbachian from Morocco (High Atlas Mountains).

Family Dermosmiliidae (Koby, 1889)

Genus Proleptophyllia (Alloiteau, 1952)

Type species. Montlivaultia granulum (Fromentel and Ferry, 1866) by monotypy.

Similarities and differences. The genus Proleptophyllia differs from other Moroccan Lower Jurassic solitary genera by the moniliform character of the distal edge of septa.

Remarks. Following Vasseur and Lathuilière (2021), we have assumed the synonymy between Proleptophyllia and Epiphyllum (Alloiteau, 1957), and we have also included Cyclophyllopsis cornutiformis (Beauvais, 1986) in the synonymy of the species.

Etymology. From pro: before in ancient Greek and leptophyllia referring to the genus Leptophyllia (Reuss, 1854).

Status. Available and valid.

Proleptophyllia granulum (Fromentel and Ferry, 1866)

|

Fig. 19 Proleptophyllia granulum (Fromentel & Ferry, 1866). A Transverse thin section of the specimen SB–342. B Enlargement of A showing the septal ornamentation. C Distal transverse section of the specimen SB–167/1. Proleptophyllia granulum? (Fromentel and Ferry, 1866). D Transverse section of the badly preserved specimen SB–326/1. |

*v. 1866 Montlivaultia granulum sp. nov. — Fromentel & Ferry, p. 136, pl. 24 fig. 2.

1866 Montlivaultia arenula sp. nov. — Fromentel & Ferry, p. 134-135, pl. 23 fig. 4.

1952 Proleptophyllia granulum (Fromentel & Ferry) — Alloiteau, p. 666.

1956 Proleptophyllia granulum (Fromentel & Ferry) — Alloiteau, Pal. univers. n∘ 121.

1957 Epiphyllum arenula (Fromentel & Ferry) — Alloiteau, p. 107, pl. 5 fig. 13.

1957 Proleptophyllia granulum (Fromentel & Ferry) — Alloiteau, p. 113, pl. 8 fig. 10, and fig. 73.

1986 Cyclophyllopsis cornutiformis nov. sp. — Beauvais, p. 34, pl. 7 fig. 1, pl. 8 fig. 1, text-fig. 23.

2011 Proleptophyllia cf. granulum (Fromentel & Ferry) — Lathuilière, p. 542, pl. 3 fig. 11–12.

.2018 Proleptophyllia granulum (Fromentel & Ferry) — Vasseur, p. 297–298, fig. 3.78.

v. 2019 Proleptophyllia granulum (Fromentel & Ferry) — Boivin, p. 254–255, figs. 10.31.

2021 Proleptophyllia granulum (Fromentel & Ferry) — Vasseur & Lathuilière, p. 1222, fig. 23.

Type designation. Lectotype MNHN.F.M03533, by inference from a holotype by Alloiteau (1956) (ICZN art 74.6).

Type locality and horizon. Pliensbachian from May-sur-Orne, Normandy, France.

Originally included material. Unspecified.

Etymology. From granulum: small grain in Latin referring to the shape of distal edge of septa.

Material examined. 2 specimens: SB–167/1 and SB–342 and 1 uncertain specimen: SB–326/1.

Ages and localities of material. Upper Sinemurian or lowermost Pliensbachian from Castle olistolith and lower Pliensbachian from Owl olistolith (and possibly upper Sinemurian from Serdrar reef), Amellagou Region, High Atlas Mountains, Morocco.

Description. Solitary coral. Transverse section of corallite sub-circular to slightly elliptical. Septa sub-compact with pennular structure, straight or slightly wavy, joined or contratingent. Hexameral symmetry. Septal apparatus organised in four size orders. Pennulae-like granules are not arranged in menianae and do not alternate between neighbouring septa. Trabecular axes are more and more detached toward the centre of corallite producing a parietal papillose columella.

Dimensions. Calicular diameter 18.7 to 19.7 mm — Number of septa 120 septa — Septal density 10 to 12 septa per 5 mm.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Upper Sinemurian — lower Pliensbachian from Morocco, Pliensbachian from France, Domerian from Morocco, Toarcian from Morocco.

Family Latomeandridae (Alloiteau, 1952)

Genus Periseris (Ferry, 1870)

Type species. Agaricia elegantula (Orbigny, 1850) by monotypy.

Similarities and differences. This genus differs from Thamnasteria (Le Sauvage, 1823) by the septal structure, typically alternating pennular in Periseris with pennular rims turned upward. A complete comparison is available in Lathuilière (1990, p. 36). The differences with Thamnasteriamorpha (Melnikova, 1971), a Triassic genus, is still a matter of discussion (Lathuilière, 1990).

Etymology. From peri: around in ancient Greek and series: row in Latin probably referring to the meandroid tendency of the genus with concentric valleys.

Status. Available and valid.

Periseris elegantula (Orbigny, 1850)

|

Fig. 20 Periseris elegantula (Orbigny, 1850). A Transverse thin section of the specimen SB–345. B Enlargement of A. C Longitudinal thin section of the specimen SB–345. D–E Enlargements of C. F Transverse thin section of the specimen SB–237. G Enlargement of F. |

* 1850 Agaricia elegantula sp. nov. — Orbigny, p. 293.

1990 Periseris elegantula (Orbigny) — Lathuilière, p. 38 Pl. 1–5, with synonymy (50 references).

1993 Periseris elegantula (Orbigny) — Pandey & Fürsich, p. 37, Pl. 11 fig. 2, text-fig 22.

2000 Periseris elegantula (Orbigny) — Lathuilière, p. 157–159, fig. 13.1–2.

2003 Periseris elegantula (Orbigny) — Pandey & Fürsich, p. 94, Pl. 26 fig. 1–6.

2005 Periseris elegantula (Orbigny) — Morycowa & Misik, p. 430, fig. 8.1–4.

? 2006 Periseris elegantula (Orbigny) — Pandey & Fürsich, p. 65, Pl. 5 fig. 4–7.

? 2011 Periseris sp. — Lathuilière, p. 540, Pl. II, figs. 5–9.

2018 Periseris elegantula — Vasseur, p. 277–278, fig. 3.70.

2019 Periseris sp. — Brame et al., fig. 7.F–G.

v. 2019 Periseris elegantula (Orbigny) — Boivin, p. 236-237, figs. 10.24.

v. 2023 Periseris elegantula (Orbigny) — Lathuilière et al., p. 30, fig. 9.C–D.

Type designation. Lectotype, by inference of a holotype by (Alloiteau, 1957) (ICZN art 74.6), MNHN.F.A26574.

Type locality and horizon. Bajocian from Langres, Haute-Marne, France.

Originally included material. Unspecified.

Etymology. From elegans: elegant and ula: a diminutive suffix in Latin.

Material examined. 2 colonies: SB–237 and SB–345.

Ages and localities of material. Lower Pliensbachian from Owl olistolith, Amellagou Region, High Atlas Mountains, Morocco.

Description. Flat or flattened hemispheric thamnasterioid colonies. Radial elements are biseptal sheets, thick, exactly confluent, subcompact, straight or sinuous, free or joined, sometimes contratingent. Pennular structure of radial elements, sub-continuous meniana with pennular rims turned upward (Fig. 20E,F). Pennulae of one septum alternate with those of the neighbouring septa. On both sides on a same septum, pennulae are not always aligned. Biseptal sheets show a sub-parallel preferential orientation between corallites (Fig. 20A). No hexameral symmetry visible. Endotheca badly preserved, perhaps made of vesicular dissepiments. Columella styliform. No wall. Remains of a holotheca are locally preserved (Fig. 20F).

Dimensions. Distance from corallite to corallite 3.6 to 7.8 mm — Septal density 4 to 6 septa per 2 mm.

Similarities and differences. Periseris elegantula is the only nominal species of the genus known for the Liassic. However, a Periseris sp. was described in Toarcian from Morocco (Lathuilière, 2011). It was kept in open nomenclature for its absence of holotheca.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Pliensbachian and Toarcian from Morocco (High Atlas Mountains), Bajocian of France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Germany, Switzerland, Slovakia, Bathonian of India, Dogger from Iran.

The new discovery of such an ancient occurrence fills the gap between the genus Periseris and the closely related Triassic genus Thamnasteriamorpha (Melnikova, 1971) (=Thamnotropis Cuif, 1975b).

Family Protoheterastraeidae (Cuif, 1977)

Genus Paravolzeia (Roniewicz et al., 2005)

Type species. Paravolzeia alpina (Roniewicz et al., 2005) nomen novum pro Volzeia (Hexastraea) fritschi (Volz, 1896) in (Cuif, 1975a), non Hexastraea fritschi (Volz, 1896), by original designation.

Originally included species. Paravolzeia alpina (Roniewicz et al., 2005) and Paravolzeia timorica (Roniewicz et al., 2005).

Similarities and differences. This genus differs from the phaceloid genera:

- Paracuifia (Melnikova, 2001) that has a vesicular endotheca, and poorly hierarchised septa.

- Thecactinastraea (Beauvais, 1986) that has septa much more ornamented.

- Phacelostylophyllum (Melnikova, 1972) that is stylophyllid in septal structure.

- Retiophyllia (Cuif, 1966) that is a distichophylliid in structure and shows a typical epitheca.

Etymology. From para: near in ancient Greek, and volzeia referring to the similarity with the genus Volzeia (Cuif, 1966).

Status. Available and valid.

Paravolzeia? alpina? (Roniewicz et al., 2005)

|

Fig. 21 Paravolzeia? alpina? Roniewicz et al., 2005. Transverse thin section of the specimen SB–219/2. |

1975a Volzeia (Hexastraea) fritschi sp. nov. — Cuif, p. 352, figs. 25-26 (non Hexastraea fritschi (Volz, 1896), p. 91, Pl. 11 figs. 14–20).

* 2005 Paravolzeia alpina sp. nov. — Roniewicz et al., p. 293. fig. 4–D, G.

2015 Paravolzeia alpina Roniewicz et al. — Stanley & Onoue, p. 21, fig. 15–a,b.

v. 2019 Paravolzeia? sp. — Boivin, p. 234, fig. 10.23.

Type designation. Roniewicz et al. (2005) strangely mentioned a lectotype for the creation of their own species. The "lectotype" would be housed in MNHN and implicitly referred to the material of Cuif (1975a). Unfortunately, in the Corallosphere website (Roniewicz, 2013), a holotype housed in Warsaw ZPAL HVIII/1 and figured in Roniewicz et al. (2005) fig. 4D, G is mentioned in contradiction with the previous designation.

Type locality and horizon. Carnian, Julian sub-stage, from Dolomites, northern Italy.

Originally included material. Only the type specimen?

Etymology. From alpina referring to the Alps.

Material examined. 1 sample: SB–219/2.

Ages and localities of material. Upper Sinemurian from Serdrar reef, Amellagou Region, High Atlas Mountains, Morocco.

Description. Fragment of colony, perhaps phaceloid. Septa thin, compact, free, sinuous. Septal apparatus organised in three size orders. S1 septa reach the centre of the corallite. Among them, some septa show a spoon-shaped inner margin, they could correspond to the six protosepta (?). S2 measure two thirds of the radius of the corallite in length. S3 are short and not always present. Lateral faces of septa lowly ornamented with possible granules. Fossa straight and narrow defining bilateral symmetry. Endotheca present made of few thin tabulae.

Dimensions. Calicular diameter circa 3 mm — Number of septa circa 30 septa extrapolated from the best-preserved sector — Septal density 3 septa per 1 mm.

Remarks. The only fragment found does not allow a firm identification.

Similarities and differences. Paravolzeia alpina (Roniewicz et al., 2005) differs from P. timorica (Roniewicz et al., 2005) that has a smaller calicular diameter (from 1.8 to 3 mm) and a poorly developped septal apparatus.

Stratigraphic and geographic distribution. Carnian from Dolomites (Italy), Norian from Japan, Sinemurian from Morocco?

Family Reimaniphylliidae (Melnikova, 1975b)

Genus Distichophyllia (Cuif, 1975a)

Type species. Montlivaltia norica (Frech, 1890): p. 39, pl. 3 fig. 8–9, pl. 10 fig. 1–5. pl. 18 fig. 7. by original designation.

Originally included species. Only the type species.

Similarities and differences. Differs from Coryphyllia by the microstructure of septa characterised by a mid-septal line in zigzag and fibrous, and laminar thickening deposits. In absence of preserved microstructure, the distinction remains difficult and we can suspect some inappropriate identifications (for instance in Deng and Zhang, 1984b). Moreover, Distichophyllia shows a septal apparatus hierarchized in thick S1 and S2 septa whereas following size orders septa are thin. Similar genera are compared in the paragraph similarities and differences of the genus Coryphyllia.

Etymology. From distichos: double row and phyllia: leaf both in ancient Greek, probably referring to usage in botany to designate a particular kind of phyllotaxy very similar to the structure of trabecular axes.

Status. Available and valid.

Distichophyllia norica (Frech, 1890)

|

Fig. 22 Distichophyllia norica (Frech, 1890). A Transverse thin section of three contiguous corallites (specimens SB–202). B Enlargement of A. C Transverse thin section of the specimen SB–159. D Transverse thin section of the specimen SB–165. E Transverse thin section of the specimen SB–203. F Enlargement of E. |

1854 Montlivaltia cupuliformis n. sp. non Edwards & Haime — Reuss, p. 102, Pl. 6 figs. 16–17.

* 1890 Montlivaltia norica nomen novum — Frech, p. 39-40, Pl. 3 fig. 9, Pl. 10 figs. 1–5, Pl. 13 figs. 1–7, Pl. 18 fig. 17.

1890 Montlivaltia gosaviensis n. sp. — Frech, p. 41, Pl. 11 fig. 7.

1903 Montlivaltia aff. norica Frech — Kittl, p. 727 and 731.

? 1911 Montlivaltia norica Frech — Vinassa de Regny p. 99, Taf. 71, Fig. 15–17.

non 1911 Montlivaltia gigas sp. nov. (non Fromentel 1861) — Vinassa de Regny, p. 98, Pl. 70 figs. 12–13.

1927 Montlivaultia norica Frech — Smith, p. 126, Pl. 111 fig. 6.

1929 Montlivaltia norica Frech— Douglas, p. 645, PI. 46, figs. 1a, 1b, & 2.

1956 Montlivaltia norica Frech — Squires, p. 21, figs. 32–47.

? 1964 Montlivaltia sp. cf. M. norica Frech — Kanmera & Furukawa, p. 120, Pl. 12 figs. 6–10.

1966a Montlivaltia norica Frech — Kolosváry, p. 182.

1966b Monilivaltia norica Frech — Kolosváry, p. 127.

1975a Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Cuif, p. 304-318, 398, figs. 2–6.

1975 Reimaniphyllia gosaviensis (Frech) — Melnikova, p. 87–89, Pl. 15 figs. 1 and ? 2.

? 1975 Montlivaltia norica Frech — Wu, p. 106, Pl. 4 figs. 6–7.

1977 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Cuif, p. 19, 39, fig. 4, Pl. 3 figs. 4–8, Pl. 4 figs. 5–7, Pl. 5 fig. 3.

p 1979 Montlivaltia norica Frech — Schäfer, p. 44, Pl. 10 fig. 1 ?, Pl. 11 fig. 2.

1979 "Montlivaltia" norica Frech — Stanley, p. 12, 24, 28, 32, 38.

? 1979 Disticophyllia cf. norica (Frech) — Montanaro Gallitelli, Russo, & Ferrari, p. 149, pl. 4 fig. 9 a–b.

1979 Montlivaltia norica Frech— Liao & Li, p. 53, Pl. 24 figs. 7–11.

? 1980 Montlivaltia norica Frech — Senowbari-Daryan, p. 39, Pl. 4 fig. 1.

? 1980 Montlivaltia norica Frech — Kristan-Tollmann et al., p. 173, Pl. 5 fig 6, Pl. 6 figs. 1, 3.

1980 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Cuif, p. 365, fig. 3.

1981 Montlivaltia norica Frech — Sadati, p. 199.

1982 Montlivaltia norica Frech — Berg & Cruz, p. 11.

? 1982 Montlivaltia norica Frech — Liao, p. 169, pl. 16 fig. 2a–c.

1982 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Buser et al., p. 21.

p 1984a Distichophyllia norica — Deng & Zhang, p. 261, Pl. 5 fig. 3? non fig. 2.

1984a Distichophyllia norica xizangensis (subsp. nov.) — Deng & Zhang, p. 261, Pl. 5 figs. 6–9.

1984a Montlivaltia tenuise (sp. nov.) — Deng & Zhang, p. 246, Pl. 2 figs. 3–6.

? 1984b Distichophyllia cf. norica — Deng & Zhang, p. 293, Pl. 4 fig. 3.

1985 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Bychkov & Melnikova, p. 161.

? 1986 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Stanley & Senowbari-Daryan, p. 173, fig. 3.

p 1986 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Stanley, p. 29, Pl. 3.1 figs. 4 and 6 non 5.

? 1986 Distichophyllia norica Frech — Xia & Liao, p. 44, Pl. 3 figs. 5–12.

1986 Distichophyllia cf. norica (Frech) —Melnikova & Bychkov, p. 65, Pl. 6 fig. 2,.

1986 Distichophyllia norica Frech — Iljina & Melnikova, p. 46, Pl. 12 fig. 1–2.

non 1986 Distichophyllia cf. norica Frech — Iljina & Melnikova, Pl. 18 fig. 1.

1987 Distichophyllia gosaviensis (Frech) — Turnšek & Ramovš, p. 35, Pl. 4 figs. 5–6.

1989 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Roniewicz, p. 39–41, Pl. 6 figs. 2–4.

? 1989 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Stanley & Whalen, p. 806–807, fig. 5.4 and 5.6.

1989 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Stanley, p. 770.

1990 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Riedel, p. 61.

? 1990 "Montlivaltia" verae (Volz) — Riedel, Pl. 11 fig. 4.

1991 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Turnšek & Buser, p. 227, Pl. 2 figs. 4–5.

1991 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Riedel, p. 114.

? 1993 Distichophyllum noricum (Frech) — Liao & Xia, p.207, fig. 2-3.

? 1994 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Stanley, p. 88, Pl. 4 figs. 3–4.

1994 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Liao & Xia, p. 54, Pl. 2 figs. 8–12, Pl. 3 fig. 8.

1994 Montlivaltia tenuise Deng and Zhang — Liao & Xia, p161, Pl. 67 figs. 2, 4–6.

? 1995 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Prinz-Grimm, p. 235, fig. 3c.

1996 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Bernecker, p. 54.

1996 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Senowbari-Daryan, p. 302.

1997 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Turnšek, p. 79, fig. 79.

1997 Distichophyllia gosaviensis (Frech) — Turnšek, p. 78, fig. 78

2000 Distichophyllia cf. norica — Blodgett et al., n° 9237

2001 Distichophyllia norica Frech — Melnikova, p. 46, Pl. 13 fig. 1.

2002 Distichophyllia cf. norica — McRoberts & Blodgett, p. 57.

2003 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Stanley & Yarnell, p 114.

2005 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Bernecker, p. 447 & 450.

2008 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Caruthers & Stanley, p.475, figs. 2.18–20, 2.25.

2009 Distichophyllia cf. norica (Frech) — Mannani & Yazdi, p. 368.

p 2010 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Rosenblatt, p. 99, Pl. 1 figs. 18–19, non Pl. 4 figs.15 & 19.

2012 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Shepherd et al., p. 807, fig. 6–1–6–3, 6–6, 6–7, 6–10 and 6–11.

non 2013 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Liao & Deng, p. 42, Pl. 10 figs. 7–10, Pl. 11 figs. 1–6.

2013 Distichophyllia norica xizangensis Deng & Zhang — Liao & Deng, p. 39, Pl. 6 figs. 11–14.

2013 Distichophyllia tenuise (Deng & Zhang) — Liao & Deng, p. 42, Pl. 11 figs. 7–11.

2017 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Bo et al., p. 272.

v. 2018 Distichophyllia sp. 2 — Vasseur, p.178-179, fig. 3.30.

v. 2019 Distichophyllia norica (Frech)— Boivin, p. 198, figs. 10.7 and 10.8.

? 2020 Distichophyllia cf. norica (Frech) — Mannani, p. 11, figs. 6-H and 6-I.

2020 Cuifia elliptica Melnikova — Mannani, p. 11, figs. 7-C —F.

v. 2021 Distichophyllia norica (Frech) — Vasseur & Lathuilière, p. 1244, fig. 40.

Type designation. Syntypes BSPG AS XII 46, 48, no lectotype designated.

Type locality and horizon. Norian — Rhaetian from Zlambach bei Aussee, Fischerwiese, Oedalm, Hammerkogel and Hallstätter Salzberg (Austria), and Scharitzkehl Alp (Germany).